Whoever You Are

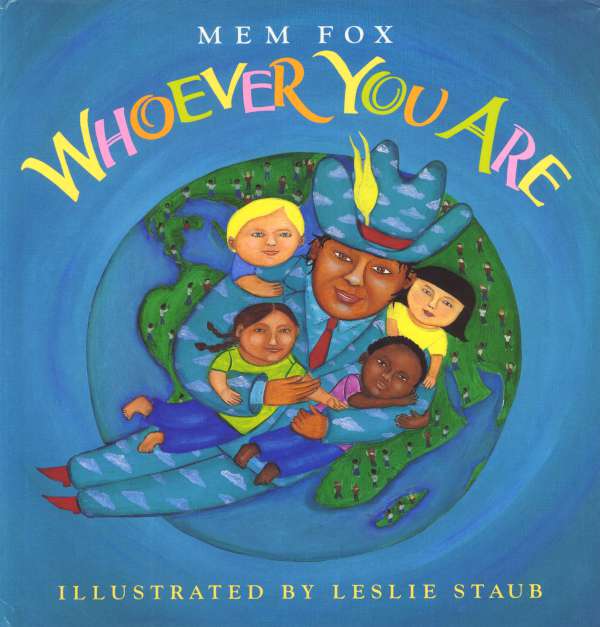

Illustrated by Leslie Staub

“Little one, whoever you are, wherever you are, there are little ones just like you, all over the world. Their skin may be different from yours, and their homes may be different from yours; their schools may be different from yours and…

Three gorgeous, different-similar Australian readers, whoever they are! ‘We are one, but we are many…

Whoever You Are was translated into Tetum, the language of the East Timorese. I visited East Timor to launch the Tetum edition

Whoever You Are is my second book about peace and equality. The first was the allegorical tale Feathers and Fools, which was aimed at an older age group. Whoever You Are is for children aged from one day (literally) to about five years old.

I come from a pacifist family who believes that tolerance is one of the great virtues, and that all people are equal and worthy of human rights and human dignity. Many years ago I read in the newspaper a shocking piece on the war in Bosnia (too shocking to reprint here) about the inhumanity of an 18 year old girl against a boy of the same age who had been her classmate only weeks before. She had become an animal in war and saw ‘enemies’ where she should have seen humans, friends, who were just like her.

I thought: “We have to get to the children, while they’re young. Teach them about the similarities between the peoples of the world, not the differences.” I imagined a tribal elder talking to a child, passing on the values of the tribe. The story-poem began to emerge.

Whoever You Are breaks new ground in children’s book illustration. It could have been sweet and sentimental but instead has freed itself from cloying predictability in a style that’s a breath of fresh air. The divergent, naive-art illustrations are by Leslie Staub, a funky New Orleans artist.

When my grandson Theo was born he was tiny and premature. He weighed one kilo (two pounds) and his arms were the size of my index finger. Every day for two and half months, to encourage him to grow and thrive, and to bond with him, I opened one of the round doors of his humidicrib and read him Whoever You Are, using the same tone of voice every time, the same rhythms and the same ups and downs. I like to think it soothed him and encouraged him to know he wasn’t alone in the world: that there were millions of other little babies out there—each was his equal, and each was ready to be his friend. I am passionate about this book and thankful that it has become and remains one of my classics.

A teacher, Adam Claridge, sent me this great story (27:07:13) about teaching Whoever You Are:

During Harmony Week I read the book to the class and then asked them to make a picture of something they liked or remembered from the book.

So off they all go to do their pictures.

As I look around the room I see that Elisabeth isn’t doing anything – she’s just sitting there. So I go over and ask her why she’s not drawing a picture.

“I don’t understand the book,” she says. “It’s a silly book. I don’t get it.”

So I go and get the book and we go through it together. I ask her what she doesn’t understand and Elisabeth points to the picture of the man with the kids in the sky.

“Why is he up there? I don’t even understand it,” she says.

And I tell he about how he is showing the kids about people around the world. So we go through the book like this and then I ask her to have another think about what she could draw and I go off to do something else for a while.

After a bit I look over and see that she is still just sitting there. When I talk to her again she says, “But I don’t like anything about it. It is a silly book.”

So I ask her, “Well, what would make it better, then?”

And she says, “Chickens. There should be chickens in it.”

So I tell her to draw the chickens that should have been in the book. And she’s happy with that.

When she is done she shows me the picture and I ask her to tell me about it and she says,” Well, these are the chickens. This one is a red chicken and this is a blue chicken and this is the green chicken and there is an orange chicken. But they are all still chickens.”

I think she understood the point of the book.

A Speech for a University Graduation

WHOEVER YOU ARE

for UTS Hon. Doc. Graduation Ceremony

Mem Fox 28:04:11

It’s a thrill to share this great day with you. It’s so wild finishing a course, holding the parchment, kissing the qualification and thinking: ‘It’s over! Fantastic! Now I can live again.’ I know how you feel. I can still remember the first time it happened to me. In July 1968 when I walked out of drama school for the last time the feeling of liberation made me feel faint. I was walking on air, not on the road. Perhaps it was because I was madly in love at the time.

Let me go even further back than 1968. When I was still a babe in arms my Australian parents packed up all their belongings and sailed away from Melbourne on a passenger ship bound for Africa. I grew up in Africa, on a mission, near a city called Bulawayo, in Zimbabwe. A mission is like a sprawling farm and the one I grew up on was called Hope Fountain. It had houses and little farms, a dairy with fabulous smells and frothing milk in huge cans, a cattle dip with wild whips cracking and cattle mooing in misery and boys yelling, a school with no resources, a teacher training college, a lovely church, red-earth football fields and netball courts, a dam, a river, creeks and snakes and eagles. Occasionally even a leopard. It was magic.

In my first year at school I was the only child with white skin. All my friends were Africans. All the games I played were African games. All the songs I sang were Africa songs and when I spoke English I spoke it with an African accent like this: “Ladies and gentlemen, I am very happy to be speaking to you this afternoon here at UTS.”

In the early fifties in Zimbabwe white children weren’t allowed to go to school with black children. The authorities found out that I was at the mission school and told my parents to remove me immediately and send me to a white school. I remember swinging on our gate as all my black friends went past my place on their way home. For the first time in my life I felt different from them. And utterly miserable. I’d never felt different before. It was embarrassing.

To make matters worse, when I went to the white school I had to wear shoes—I hated shoes—and of course I spoke with this African accent and I was laughed at and teased and bullied. I remember sitting in the girls’ toilet and crying very quietly so no one would hear me. My heart was broken. I was six years old.

I think I knew by the age of six that I wasn’t different really. I knew we were all kids. I knew some kids were great, some kids were mean, some were good at sport, some were good at art, and others were terrific at reading or maths. I knew, deep down, that skin colour made no difference and I wondered why adults and the government thought that it did.

Since those days I’ve met many people, in many lands, in many cities and towns and villages and schools and houses and the thing that’s struck me is not how different we are, but how similar.

A few years ago I was in Yemen, an Islamic country where the girls wear a head-to-toe black burka in such a way that you can’t even see their eyes. We were passing a girls’ school as they were all coming out at the end of the day and I noticed that the way they talked and laughed and giggled and gossiped, even the way they moved was exactly like high school girls in Australia. Even though their religion was different, their clothes were different, their food was different, their houses were different and their skin was different, they were just like us.

In Vietnam one hot evening I watched five older boys play soccer in the street. They were yelling and laughing and concentrating and dribbling that ball in the way Aussies guys play with soccer balls. Vietnam is a Buddhist country but watching these boys I realised that even though their religion was different, their clothes were different, their food was different, their houses were different and their skin was different, they weren’t different at all: they were just like us.

A few years ago I did some work in a school in China and when I was out for a walk I saw parents out walking too, with their babies all wrapped up against the cold. And they talked to those babies and cooed at them, and were crazy about them, and kissed them and were proud to show them off to their friends. And I realised that even though their religion was different, their clothes were different, their food was different, their houses were different and their skin was different, they weren’t different at all: they were just like us.

And yesterday in the supermarket I saw a man who was so fat that I found myself staring at him even though I didn’t mean too. Why are you so damn FAT? I thought. And then I looked at him and I realised that he too had a head, two legs, two eyes, and hair and that his heart was beating and keeping him alive, like mine was. And I knew that even though his food is different, his clothes are different, and his life is different, he wasn’t different at all: he was just like me.

And I remember an Iraqi refugee named Moyad, aged 20, whom we had been looking after. He’d only been in here for a couple of years, mostly at the Baxter Detention Centre in South Australia. My husband made a joke and Moyad looked at me and said: ‘He’s a cheeky little Vegemite, isn’t he?’ And I knew that even though his past was different from ours, his skin is different from ours, and his religion is different from ours, he has the same sense of humour as all my close friends. He’s fabulous to be around. He made me laugh like a drain. He’s just like you. He’s just like me.

If we stay in the same suburb all our lives, and always hang out with the same crowd, we never get to see the amazing world beyond our front door. We never understand the thrilling differences that make us, in the end, understand the our similarities. So I’m begging you please, to get out of this place—even for a short while—get out of this town, out of this state and out of this country, and breathe another air before you die of boredom or start being boring yourself. Then come back and revel in the differences you’ve experienced and world you’ve come to know.

But while you’re out there, remember this, and remember it here, as well: if you see someone different from you in any way and it makes you feel uncomfortable, or superior, if you find that difference scary, or disturbing, relax! Instead of your antennae going: ‘I don’t want to know that person,’ remember, whoever you are, wherever you are, that that person is exactly like you, with the same troubles, the same fears, the same longings, the same miseries, the same laughter, and exactly the same tears. People who are poor, people who barrack for the wrong football team, people who worship the same God in different ways, people who are guys, people who are anorexic, people who don’t have the latest play station, people in wheelchairs, people who are snobs, people who are Olympic medallists, people who drive beaten-up cars, people who are rich and famous, people who are suicidal, people with iPads and people without them, people who are Botoxed, people who—even as I speak—are being killed in Syria, Africa, Iraq, Israel, Palestine, Libya and Afghanistan, even people like your mother and all your lecturers, be they frisky or august—none of them is different from you! They’re not different from me. We are all the same.

If we focus on our likenesses instead of our differences we’ll get along better whether we’re in pairs, in small groups or in nation states. Across the world we’ll be far less isolated and stupid and crass and pathetic than we tend to be much of the time. We’ll be kinder, more sensitive, more sensible, more tolerant, more helpful and more forgiving. Our refugee policy will be empathetic and compassionate instead of cruel, idiotic and short-sighted.

In case we need one last reminder about the absolute bliss of being like other people instead of suspiciously different from them, I’ll end with a very short book written by me called WHOEVER YOU ARE: read it.

That’s it, basically. I have incredible faith in you all. You’re young. You’re smart. You’re switched on. I need you to fix the climate, keep the rain falling, invest in alternative clean energy, be kind to the world and to each other, and visit me when I’m old, OK?

Congratulations on finishing your current studies, whoever you are, wherever you’re from, and all the very best for the future, wherever that may take you in this big wide world. Thank you for having me.